If you wander around the historical sections of Mankato, it doesn’t take long to come across Randy Dinsmore’s handiwork. Whether it’s the Cray Mansion, a residential home in the Lincoln Park District or even the historic Hubbard House, Dinsmore has spent more than 30 years restoring buildings as a project manager at Goodrich Construction.

“I am fascinated by some aspects of history and bored stupid by others,” Dinsmore admitted. “That’s the way of it, I suppose. Everybody likes to look at all of this stuff inside the Hubbard House, but I’m not really interested in the contents. I’m interested in the building itself. What excites me is when I tear open the deteriorated skirt around the bottom of the bay window and find a piece of lumber that was stained and varnished and clearly had been trimmed in something else prior… It had a previous life before the 1880s when it became part of this bay window. I find it fascinating to open something like that up and find this stick in there that had a history before it even became part of that building over 100 years ago.”

Preserving the Past

Dinsmore has worked with Goodrich Construction since 1981, with a “couple years” in construction prior to that. During his early days at Goodrich, the company started venturing into historical restoration projects, working on places such as the Cox House in St. Peter. As their restoration reputation grew, they expanded their range up to the Twin Cities and as far as Windom, St. James and Faribault.

“Once we developed a reputation, people came looking for us for the historical restoration,” Dinsmore said.

I am fascinated by some aspects of history and bored stupid by others. … Everybody likes to look at all of this stuff inside the Hubbard House, but I’m not really interested in the contents. I’m interested in the building itself.Randy Dinsmore

One of their most enduring projects has been with the Hubbard House in Mankato. Dinsmore said they’ve been working on different parts of the building for more than 25 years. Recently, they replaced all the rubber roofing and restructured the carriage house, which was suffering from a broken roof. As part of the project, Dinsmore was hired to carve grapevine panels to replace deteriorated materials on the outside of the building.

But the work is far more extensive than that. Dinsmore and his team have partially restored the Hubbard House’s office porch, redone the office roof, restored the kitchen porch and redone the front porch completely, including rebuilding all the rails and columns. They’ve removed all of the iconic multi-colored slate on the roof and reinstalled new slate. They also restored the balustrade, or “widow’s walk,” on the upper roof, a part of the design that had been missing for decades.

“There were a few fragments around, so we had patterns to work from, but the bulk of it had rotted out,” Dinsmore said. “We recreated that and put it up there.”

This wasn’t the only time that Dinsmore and his team had to do some research to figure out what the original building looked like. He said that the house’s dormers, the roofed structures that contain windows and extend beyond the plane of a pitched roof, originally had crests at the top, but they had been missing for at least 50 years. When it came time to restore the roof, he needed to consult grainy old pictures to come up with as accurate a pattern as possible.

“[The crests] were visible in old pictures, but that was the only evidence that we had of those, so I had to invent the pattern,” he said. “The way that they’re carved and shaped was invented from smudges I could see on old photographs. It’s an educated guess at best as to what was up there originally. It’s the right basic form and size.”

Dinsmore and his team always try to be as accurate as possible when restoring history. Working with the Blue Earth County Historical Society, Goodrich Construction was able to hunt down the original quarry that the Hubbards used when first installing their roof slate so that the new slate could come from the same place.

“There are a handful of leftover pieces, both of the new material and some of the old pieces, down in the basement of the Hubbard House,” Dinsmore said. “An interesting discovery that we made, when we started recording the pattern that those had been laid up in, we discovered that not every surface of the roof was done with the same pattern. I don’t know if they did it to use up the material they had available or why, but we discovered that the pattern varied from side to side of the roof. It was not something you’d ever have noticed if you weren’t looking for it. We had to decide how to put it back together, so we established the most common pattern and redid the whole roof in that pattern.”

While Dinsmore has spent a considerable amount of time on the Hubbard House, he said his favorite restoration project was actually 202 North Third Street in St. Peter. Known as the “Schumacher House,” the structure was built in 1887 and is still used as a residential home. During the 1998 tornado, it was badly damaged, with much of the roof destroyed and many windows shattered.

“[The tornado] dropped fascinating architectural details all over the yard and the street and blew some of them clean off the block,” Dinsmore said. “For me, it was a rare opportunity. When I’m restoring architectural details, I almost always have at least the original pieces there. Even if they’re rotted out and need to be replaced, I at least have something to work with for patterns. But in this case, a lot of the materials were just plain gone, so a lot of it was recreated from photographs.”

Besides photographs, Dinsmore was also able to study the original building blueprints, but he quickly figured out that the building did not perfectly match the blueprint, which meant that he now had to figure out exactly what was where. The project took 13 months and almost completely rebuilt the house. Dinsmore created a new copper onion dome for the house’s tower, hand-carved grapevines, scalloped arches and sunburst patterns done with siding.

“I did all kinds of fascinating little stuff,” he said.

A Different Way to Restore

When Dinsmore isn’t restoring old homes, he has found another creative outlet: beautiful hand-crafted wooden bowls. While much of his raw material comes from trees he cuts and cures in the area, he has also come up with a special method to restore rotting or deteriorated wood into a good enough condition to craft a new bowl out of it.

“One of the bowls that I’ve made is from a rafter off of the front porch of the Henry Ladd House [in Minneapolis],” Dinsmore said. “This wood would have been a living tree during the Dakota uprising. In 1885, it became a rafter on the Henry Ladd House, and 130 years later, I pulled it out of there in the process of rebuilding the deteriorating structure on that front porch roof. I removed all the square steel nails from it and… solidified and stabilized the pieces, and I turned a lidded bowl out of it.”

There’s a guy who lives a couple hours south of Mankato, who brings me interesting chunks of wood, mostly off his property, and asks me to make pretty much whatever I want out of itRandy Dinsmore

Dinsmore has been doing lathe work “for fun” for many years, though he said he really got into crafting bowls about 25 years ago after a local woodworker gave a short demonstration at Goodrich Construction.

“I had just played around with a lathe, since we’ve needed to recreate some turned elements for restoration of historic properties,” Dinsmore said. “I really didn’t know what I was doing. Then [the instructor] came in and did that little training session… He didn’t do in-depth training, but it piqued my interest again.”

He added that he has crafted a special technique to restore “unusable” wood, using cactus juice stabilizing resin. This heat-activated epoxy resin stays liquid until it’s heated to 200 degrees, and then it turns solid. Dinsmore submerges a rotting piece of wood into the resin and then puts it in a vacuum wrapping chamber, where all the air is pulled out of the wood. After 24 hours to two weeks, depending on the condition of the wood, it stops making bubbles and Dinsmore releases the vacuum, letting the resin saturate the wood all the way to the core. After the resin soaks in, he places the wood into an oven to set the epoxy.

“This wood, that’s deteriorating to the point it’s crumbling, can be solidified to the point where it’s bone hard again,” Dinsmore said. “This is where my work in historic restoration kind of applies, where it intersects with the bowls. I run into a lot of deteriorating wood at work, and I played around for years with various techniques for consolidating, replacement, epoxies, resins and processes to try to reconstitute these deteriorating woods. One of the nice things about what some people call worthless wood… all of that deterioration adds a lot of color and interesting patterns. I find that fascinating. I always like working on the edge of decay like that.”

Dinsmore has used this technique on several restoration projects, including work on the Hubbard House’s front porch.

According to Dinsmore, it’s hard to estimate just how long it takes to craft a bowl, since it depends on how intricate the bowl is. An extremely simple bowl might only take two hours, while a complex bowl can take upwards of 25 hours to complete—not including the time that Dinsmore allows the half-finished product to cure, which can take from six weeks to six years.

Dinsmore said that bowls are the bulk of his work, though he does some other free form vessels as well. He occasionally takes commissions, though usually people will ask him to use a piece of wood and not request a specific end result.

“There’s a guy who lives a couple hours south of Mankato, who brings me interesting chunks of wood, mostly off his property, and asks me to make pretty much whatever I want out of it,” Dinsmore said. “He buys [the finished product] and gives it as gifts.”

Dimsmore’s work is available at his Amazon shop, RDinsmWoodArt, as well as in the gift shop of the Blue Boat in Mankato. Interested customers can also contact him at rdinsmWoodArt@gmail.com.

Additional Links

- The Hubbard House on MankatoLIFE

- The Cox House on MankatoLIFE

- Blue Earth County Historical Society on MankatoLIFE

A Heavenly Model

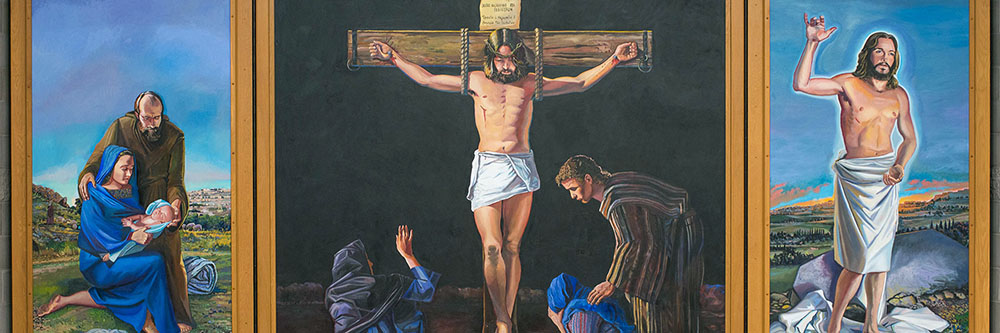

Dinsmore has one more claim to fame in the Mankato area: he holds the center space in Bethany Lutheran’s Trinity Chapel.

Technically, that’s Jesus featured on the three-piece altar triptych that was designed and painted by Bethany professor William Bukowski, but Dinsmore posed as Bukowski’s model.

Dinsmore explained that in the early 1990s, he took a sculpture class at MSU-Mankato and ended up showing one of his pieces at a show at Bethany. There, Bukowski saw him and hunted down his contact information.

“He thought I looked like a good Jesus model,” Dinsmore said. “I was wearing my hair pretty long at the time. He called me up out of the blue and asked me, ‘Do you mind if I crucify you?’ It’s kind of strange… At the time, I was a 33-year-old carpenter.”

Dinsmore said that most of his modeling consisted of standing in different poses as Bukowski took pictures of his hands, feet and forearms. He was only needed for a couple of hours, and he didn’t even see the finished result for years.

“Years later, I did visit it,” he said. “I guess it looks fine. I look a little different now. I’m a little shorter and I’m a little thicker, and my hair’s a little shorter and grayer.”